Why We Drive Pt 1: Flourishing

The Thrill of Virtue

What is at stake is not simply a legal right, but a disposition to find one’s way through the world by the exercise of one’s own powers.

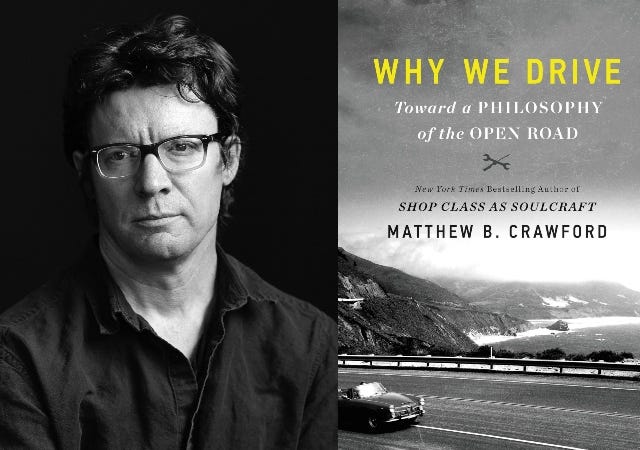

Matthew Crawford, author of a few great titles including Shop Class as Soulcraft, wrote a book back in 2020 that's just excellent, and right for the time we are in: Why We Drive. I could probably read through this a number of different ways but I am fascinated by a certain train (or perhaps road) of thought - let's get going.

(All quotations are from Why We Drive)

We are in a unique spot with automobiles, entering the very real possibility of self-driving cars on the road in a serious way. Crawford is pausing and asking: why do this? He isn't asking so much why we move from place to place, but rather, why do we do the driving rather than outsource it? Is it just because we haven't gotten there yet, or perhaps, there are real goods that the car as we know it (or knew it) provide us.

Crawford strikes right at the heart. This isn't a book about the numbers or feasibility of automation. He is asking if automation is a noble end. Crawford seems to think that cars help our spirits live - not just our bodies.

But remember, all rats die. Not every rat lives.

The goal we are after is not continued existence - but flourishing.

Flourishing - that of rats and humans alike - seems to require an environment with "open problem spaces" that elicit the kinds of bodily and mental engagement bequeathed us by evolution and cultural development.

The road as we know it - as opposed to rails or self-driving cars - can be such an open problem space:

When the traffic lights go out during a storm, it sometimes feels like waking up from a long slumber. We realize that we can work things out for ourselves, with a little faith in one another. Recall that Pope Francis called the prudent drivers of Rome, who "express concretely their love for the city" by moving through it with tact and care, "artisans of the common good." The common good may be understood in this way, as something enacted by particular people who are fully awake. Alternatively, it may be understood as something to be achieved by engineering herd behavior without our awareness, in such a way that prudence and other traits of character are rendered moot. Our role will be to step out of the way gracefully, and in this way help "optimize the output of large tools for lifeless people," as Ivan Illich wrote.

Crawford again echoes here that the development of virtue is not something we can enact or force with technology. It is only something we can provide the soil for which it to take root and grow in.

In the Aristotelian perspective as elaborated by William Hasselberger, virtue doesn't consist of a collection of true propositions that can be combined with circumstantial detail and entered into a moral calculus, to be solved by the application of universal principles, yielding an output consisting of the right action. Virtue is more like a skill, acquired through long practice in the art of living.

Life - true life of virtue - is risky.

The openness of the problem space is opened really when we remove the traffic lights and stop signs, or when we operate equipment more at the limits. Crawford at points even proposes interesting alternative policies: could we have graduated drivers licenses, where how fast you are allowed to go is determined by how proficient you are at driving? The rules of the road have already sacrificed some of the open problem space for flourishing at the technocrats' altar of security.

Crawford recounts many stories of men's (and women's) interactions with machines - mostly inspiring. But he closes with a beautiful one:

It was a slalom through the redwoods, dappled sunlight playing on perfect black tarmac as I came hard out of a corner, front wheel lifting off the ground. On this stretch of road, there are several serpentine sections where you can see, in a single take, a series of three corners ahead in their entirety, with nowhere for surprises to hide. These chicanes have a bodily rhythm to them that is sublime, when taken at speed. I have never been a good athlete, and can only admire those who move with natural grace. But on a sport bike on a canyon road, for a brief spell I feel raised up from my God-given mediocrity. By a machine! What a miracle.

I think that Crawford sells this short at the end - because the mastery on display is not like that of an athlete: it is that of an athlete. And I think it is even unfair to say that he is lifted by a machine - rather, he elevates the machine into such a beautiful display. This is obvious - the bike does nothing of its own volition. It needs a driver. This creates a relationship between him and the bike that is sublime.

Rollercoasters are neat, but they have nothing on road vehicles. A passenger and driver may experience the same G-forces, but the relationship they have to them is wholly different.

To drive is to exercise one's skill at being free.